Carmel Swann moved to Texas in June 2021 looking for a fresh start and a chance to leave bad decisions behind. But, within weeks, she was in the Harris County Jail after an altercation with the man she’d moved in with. Then, she discovered she was pregnant from a prior relationship.

She began working on a deferred adjudication agreement with prosecutors that would allow her to avoid conviction and be released in May 2022. But her due date fell in March, so she asked a family member to come from California to care for the baby during the two-month gap.

Shortly after delivering her son at the county-owned Lyndon B. Johnson General Hospital—on March 10, 2022—a Texas Department of Family and Protective Services (DFPS) caseworker told her that no one, including the Californian relative, was coming to help. The father was uninvolved, and Swann didn’t know anyone in Houston.

Overwhelmed, she felt alone and out of options. “It was just too much in that short frame of time,” she told the Texas Observer.

Her son remained hospitalized after she was returned to jail because he’d been exposed to COVID-19 and suffered a fall from Swann’s hospital bed. At the behest of the state caseworker, a representative from a nonprofit faith-based child placement agency, then called Loving Houston Adoption Agency, soon visited Swann in jail, according to a document filed in a subsequent lawsuit. (Loving Houston Adoption Agency was later renamed Loving Houston Foster and Adoption Ministries.)

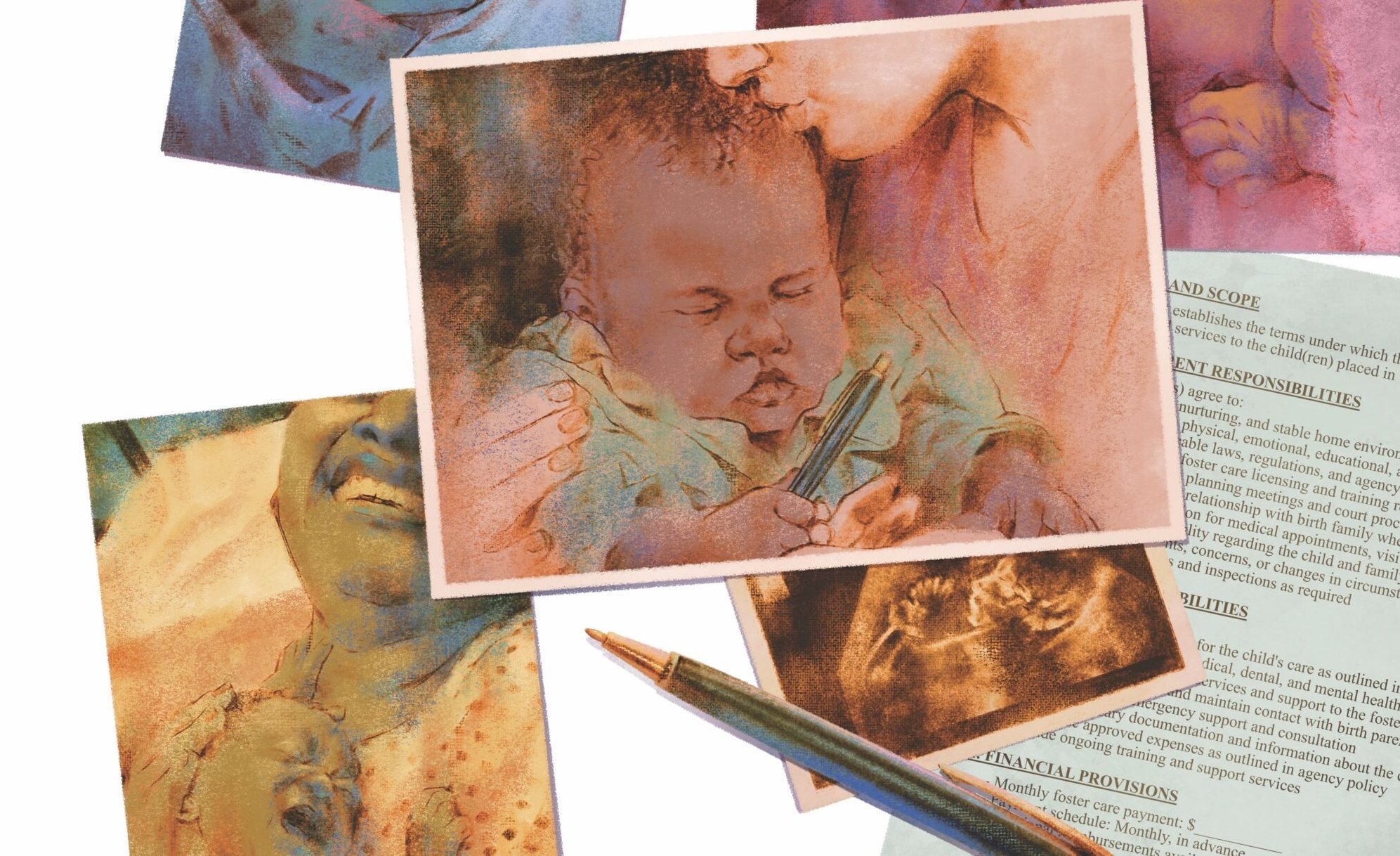

As Swann recalls it, the agency representative promised to find safe, temporary care for her child. Having grown up in California’s state-run public foster care system, Swann believed he would be safer in private placement than with the state of Texas. She thought the contract ensured that she would get him back in six to 12 months, and she signed it without consulting an attorney.

Several weeks later, her baby went to live with a former professional football player and his wife in a Houston suburb who signed their own contract to temporarily care for children brought into the agency’s fold.

Swann convinced herself things would work out. “This is going to be okay,” she remembers thinking. “I’m going to get out … and I’m going to work on getting him back.”

But, by signing the Loving Houston Adoption Agency placement contract, Swann had unknowingly entered a murky legal world.

The Observer has investigated Swann’s case and another involving a teenage mom. Both mothers were approached by private parties shortly after delivering babies in Houston hospitals, and both were later sued by couples seeking permanent custody of the children.

In more than a dozen interviews, attorneys and family preservation and child welfare advocates told the Observer they are increasingly alarmed that many women in vulnerable situations are at risk of losing their children to a privately run shadow foster and adoption system that in Texas is operating with little oversight or regulation. It’s a situation that could worsen as pregnant Texans face severely restricted reproductive care options and political power has coalesced around private child-placing agencies, crisis pregnancy centers, and adoption-centric policies, said Renee Gelin of Saving Our Sisters, a nonprofit that works with families considering adoption.

It’s too early to measure the long-term impacts of the 2022 overturning of Roe v. Wade on the U.S. private adoption industry, said Gretchen Sisson, a qualitative sociologist with the University of California, San Francisco who’s studied trends in abortion and adoption for more than a decade.

But, in Texas at least, private adoptions have already increased somewhat. There were around 7,168 adoptions in Texas in 2023, the last year for which data is available, according to the National Council For Adoption. Of those, 4,181 adoptions were of children or babies in state-run foster care. Another 2,864 were in private care, a 7 percent increase from the previous year.

The U.S. adoption industry is growing rapidly—as are its revenues. IBIS World estimated in March 2024 that the industry, which it described “as predominately nonprofit,” had realized just shy of $25 billion in revenue nationwide for 2023, with steady increases reported since at least 2018 and more growth projected.

There is no federal licensing or oversight of the growing private child-placement and adoption industry.

“The whole system is premised on commodifying human beings, regardless of whether or not it’s a for-profit or a nonprofit agency,” said Sisson. “And anytime you’re talking about people as a commodity, I don’t know what that looks like to do ethically.”

In Texas, these private organizations are supposed to be licensed by Texas Health and Human Services (HHS) in order to arrange adoptions or foster care, according to Thomas Vazquez, an HHS spokesman. Loving Houston Foster and Adoption Ministries does have a license, he told the Observer.

But that rule seems underenforced, according to documents and interviews. In the other case investigated by the Observer, a couple suing to take custody of a child born in Houston claims to have used a Florida adoption agency that is not licensed to operate in Texas.

More than 20 years ago, the state attorney general’s office and the state healthcare agency both declined to intervene when a San Antonio resident raised concerns about unlicensed adoption agencies advertising in Texas, records show.

Prospective foster and adoptive families often pay hefty fees to private child-placing agencies, and they typically do not receive funding, counseling, or other support like that offered to foster parents in the state system. IRS 990 forms show that even private agencies that are nonprofits report huge incomes from private adoptions, generated from those fees, private contributions, tax credits, and government subsidies.

The Fort Worth-based Gladney Center for Adoption, a national nonprofit organization, lists an “all-inclusive fee” of $57,500 to adopt a child. The nonprofit reported nearly $28.5 million in revenue and a net income of more than $8.6 million on its 990 for 2022-23.

Loving Houston Foster and Adoption Ministries charges $20,000 for people who seek to “foster to adopt” a baby younger than 3, and $25,000 to adopt a child of the same age, according figures posted on the nonprofit’s website in May. However, it’s hard to tell how much of the nonprofit’s income comes from adoption and foster services from its 990s. That’s because the organization is part of a larger nonprofit called YWAM Houston, a nonprofit organization that also includes Little Footprints, a ministry to the homeless that says it “assists street babies” and helps moms access resources. Little Footprints also makes referrals to the Loving Houston adoption agency, according to the latter’s website.

Loving Houston Foster and Adoption Ministries declined to comment about its fees or income, and did not provide information for this story. “The case to which you are referring is ongoing, and so we are not at liberty to comment,” Kelly Porter, director of the organization, wrote in an email.

According to a history posted on the group’s website, its founder, Kim Dale, along with her husband Martin, has worked with birth moms and children since 2001 through Little Footprints. The site also says Kim Dale previously worked for another private adoption agency in Houston.

There are more than 160 licensed private foster care and adoption agencies in Texas, according to HHS. Some partner with state agencies like DFPS, while others do not. In recent years, Texas and other states have been channeling more taxpayer funding into private child-placing agencies and crisis pregnancy centers, the latter being nonprofits which offer services to women but ultimately seek to deter them from seeking abortions. This past legislative session, Republicans earmarked $180 million for crisis pregnancy centers in the new state biennial budget, a $40-million bump from current levels.

“SHE IMMEDIATELY, AFTER HER RELEASE, TRIED TO LOCATE [HER DAUGHTER].”

Initially, Swann felt good about the arrangements she’d made for her baby. Swann began attending an outpatient drug rehabilitation program at the Houston-based Santa Maria Hostel, a 70-year-old nonprofit substance abuse treatment center for women, as part of a plea deal under which the criminal charge against her would be dismissed in 2026 if she met certain conditions. In early October, she moved into the hostel, one of several such programs that work with the state to provide parenting support and other services for women in the process of reunifying with their children.

It felt like the new beginning Swann had been dreaming about. Her son could visit her there, and they could eventually live together in a safe environment. With support and counseling, she hoped to become the mom her son deserved.

By October 13, a Loving Houston Adoption Agency caseworker had begun discussing reunification with Swann, according to an email included in court filings. Notes included in that email indicate that same caseworker had just recorded a positive impression of Swann’s interactions with her son. “I was so happy to be seeing my son,” Swann said during a recent interview. “We were almost there.”

Only five days later, on October 18, the couple who had been caring for Swann’s son filed a lawsuit in Fort Bend County district court, seeking to control the visitations—and to keep her child.

And, in her legal struggle to recover her son, Swann isn’t alone.

On May 15, 2021, a 14-year-old Guatemalan immigrant and rape survivor gave birth to a baby girl at HCA Houston Healthcare West, a private for-profit hospital in West Houston.

Three days later, a stranger visited her at the hospital, according to court documents and interviews with an attorney representing the teen mother. At the time, the girl spoke only K’iche’, a Mayan language, and Spanish, said Michael Schneider, a former juvenile court judge and a partner at the Houston law firm Connolly Schneider Shireman LLP, who represents the girl.

She was presented with a form called “Authorization By Mother for Release of Child to Third Party.” The document was written in English, which at that point she did not speak or read, Schneider said.

At some point, the girl’s name and address were printed in the spot designated for a signature, according to a photo of the document obtained by the Observer. She is not being identified here because she was a minor at the time and is a sexual assault victim.

The couple who ended up taking the baby would later claim in related court documents that they were told via phone there was a newborn available for adoption at the HCA hospital by a company called Lifetime Adoption.

Lifetime Adoption Inc. is a for-profit Florida company, according to other court documents, its website, and state records. The company’s founder, Mardalynne “Mardie” Caldwell also has been associated with an older entity named Lifetime Adoption LLC since 1986, according to the website.

Shannon and Daniel Phillips, who are from Louisiana, say they were told a “social worker employed by the hospital” was involved. They went to the hospital where they were allowed to “hold the baby,” and they hired an attorney to help them facilitate the paperwork, according to court records.

It’s unclear how Lifetime Adoption heard about a baby born in a private Houston hospital. The company did not answer questions the Observer emailed for this story.

In an email, Marsha Buchanan, a spokesperson for HCA Houston Healthcare West, denied that the hospital had any “contractual relationship with the adoption agency you are asking about.” Buchanan did not respond to specific questions about corporate policies for allowing representatives of private adoption or foster care firms access to hospital patient rooms, new or expectant mothers, or newborns.

In interviews, experts questioned the ethics of private operators obtaining access to mothers and newborns in institutional settings like hospitals and rehabilitation centers, where there are privacy rules under both state and federal laws that supposedly protect patients.

Historically, poor mothers, including immigrants and women of color, have more often been targeted both by public child welfare agencies and private child-placing agencies, said Katie Burns, founder of The Family Preservation Project, which focuses on helping women make informed decisions before agreeing to relinquish their children.

“It’s because we have a society, we have a culture that has very elitist, eugenic views on parenthood. We have the ‘haves’ and ‘have nots.’ It’s like: ‘Maybe they weren’t treated fairly, but at least that child is now in the haves,’” said Burns.

A photo of the form where the young Guatemalan’s name appears indicates that custody of her newborn was turned over on May 18, 2021, to HCA Houston Healthcare West—the hospital where she had delivered the baby just three days earlier. But the document does not mention termination of parental rights or adoption. In fact, it states: “I understand this is NOT [sic] a relinquishment of my rights as a parent.”

Buchanan did not answer a question about why or when the hospital assumes custody of a baby.

Texas law allows girls younger than 18 to give up custody of their babies without parental consent—though state law still requires girls to seek parental permission to obtain birth control. New mothers in Texas are required by law to wait 48 hours before signing contracts terminating their parental rights or relinquishing custody.

Schneider concedes his client might have thought she was agreeing to a temporary placement. However, he said, she has consistently said she never wanted to give up her baby for adoption.

He began representing the teen in 2024 when the court appointed him to represent her in the lawsuit filed by the Phillipses, the Louisiana couple, in Harris County district court seeking to terminate her parental rights.

The Phillipses took care of the baby for about 10 months in 2021 and 2022. “We were licensed foster parents, licensed through Lifetime Adoption,” they later stated in a deposition that is part of the lawsuit. Among other things, their lawsuit alleged that the teen voluntarily left the child alone or in the care of others for at least six months; “knowingly allowed” her daughter to remain in conditions that were dangerous to her health; and “voluntarily left the child alone or in possession of another without providing adequate support for the child” based on their history of having cared for her daughter as an infant.

Caldwell—who’s long been associated with similarly named entities—and others established Lifetime Adoption Inc. in Florida in 2014.

No entity called “Lifetime Adoption” is currently licensed as an adoption or foster care provider in Texas, a spokesman for HHS told the Observer in an email. The spokesperson could find no record that such an organization had ever held a Texas license. The company is licensed under the name Lifetime Adoption Inc. in both Florida and Arkansas, per its website.

Linda Rotz, director of adoption services at Lifetime Adoption, replied to an initial Observer email saying she was not familiar with the case and adding that, “We do have to honor confidentiality in all cases.” She did not respond to follow-up questions the Observer emailed to her for this story about the group’s involvement in the Guatemalan mom’s case or about the organization’s status as an unregistered adoption or foster care business in Texas.

On its website, the company says it “partners with licensed adoption agencies and attorneys nationwide, allowing us to serve adoptive parents and mothers considering adoption nationwide.”

Caldwell is also named in public records as the founder or co-founder of older Lifetime Adoption entities in Nevada and California.

Elizabeth Jurenovich, of Abrazos Adoption Associates in San Antonio, told the Observer she sent letters to both the Texas Office of the Attorney General and to state health department officials in 2000, asking them “to intervene in what appear to be blatant instances of inducement and unlicensed child-placement planning” by out-of-state entities. Jurenovich named several individuals and organizations in the letters, including Mardie Caldwell and an entity called “Lifetime Facilitation Center” in California. Response letters from both Texas agencies to Jurenovich indicate they declined to investigate.

In court filings, Shannon Phillips says she wasn’t physically present in the teen’s hospital room when the contract was presented to the teen in 2021, although Phillips’ signature appears next to a notary stamp on the document. It appears that Phillips was allowed to leave the hospital with the baby, according to other court records.

HCA Houston Healthcare West is part of the Nashville, Tennessee-based HCA Healthcare, which operates 186 hospitals and approximately 2,400 sites of care in 20 states and the United Kingdom. Buchanan, who is also an HCA division media representative, said that HCA was unaware of the allegations made in Harris County civil lawsuits over the custody of the teen’s baby and of the description in the lawsuit of their role in the foster care contract. “We are not aware of, nor a party to the litigation you are referencing.”

DFPS investigated the circumstances surrounding the teen’s pregnancy, which occurred while she was in her father’s custody. Schneider said the teen was placed in the Texas public child welfare system a day or two after the document about her baby was filled out, after which she was assigned an attorney through the court for DFPS proceedings. That attorney no longer represents her. The teen located the Phillips family, with her first attorney’s help, and made efforts to regain custody of her baby.

“She immediately, after her release, tried to locate” her daughter, said Schneider, who was not the teen’s attorney at that time.

The Phillipses were ordered to return the baby, and they did bring the child to a hearing on November 4, 2021, according to Schneider.

During the hearing, Dena Fisher, an associate judge for Harris County’s 315th District Court, denied the Phillipses’ request to intervene in the DFPS case involving the teenager and her daughter, saying that the teen “withdrew” her permission for the Phillipses to care for the child, according to the court transcript.

However, because DFPS had not secured a foster care placement for the child that Fisher found acceptable by the time of the November hearing, she allowed the Phillipses to continue to care for the baby until DFPS found new foster parents who could provide a home for both the teen and her baby.

At the hearing, Fisher said the Louisiana couple would be ineligible to sue again for custody based on their time caring for the child while the state sought another placement.

“If that were the case, I could go kidnap a child from the playground and keep it for six months and then file for adoption,” Fisher said, per the court transcript. “They don’t have permission to have the child, so they don’t have standing.”

When the state agency secured a new placement in March 2022, the couple was again ordered to return the baby, who by then was about 10 months old, and a joint managing conservatorship to provide for the little girl was established between DFPS and the teen mother.

But the Phillipses have continued their efforts to terminate the teen’s parental rights and adopt her daughter ever since, court records show. Over time, the couple has made a series of claims in court to justify their pursuit of the little girl, including alleging that the teen abused her daughter and that she had abandoned her for the first six months. The couple also sought DFPS’ removal from the case, saying that the agency “allowed” the baby to be abused, records show.

In an April 7 court hearing that the Observer attended, Michael Ejeh, an attorney representing DFPS, told Judge David Farr, the retired visiting judge hearing the case, that there has never been any evidence that the teen abused her daughter and there has never been a finding from any state authority that she is an unfit parent or a recommendation that she be stripped of her parental rights.

But the teen was not present at the hearing: Shortly before, the mother, who had chosen to remain in a foster home after turning 18, disappeared with her now 4-year-old daughter.

In court, the Phillipses’ attorney, Erinn G. Brown, repeatedly suggested that both the DFPS lawyer and Schneider were somehow complicit in the girl’s disappearance. Both vigorously denied those accusations in court or in interviews. Brown made clear that the Phillipses would continue to seek custody of the child even though the whereabouts of the teen and her child were now unknown.

Brown declined multiple requests for interviews with her or her clients.

During a phone call the day after the hearing, Schneider said he hadn’t spoken to his client since she disappeared and he had no knowledge of her plans. He wouldn’t speculate about her disappearance beyond saying that she “was constantly dealing with anxiety” because she “feared someone would take her baby.”

Meanwhile, Carmel Swann is still fighting in a Fort Bend County district court to regain custody of her son, three years after signing a contract for what was supposed to be a relatively brief foster care placement.

In all this time, there has never been a recommendation from DFPS that Swann lose her parental rights, said Tiffany Cebrun, an attorney with the Foster Care Advocacy Center, who has represented Swann pro bono since shortly after the lawsuit was initially filed.

In fact, even Loving Houston Adoption Agency was caught off guard by the couple’s lawsuit and demanded that the pair adhere to the foster care contract they had signed, court records show. That contract stated, among other things: “We agree that Loving Houston Adoption Agency has the right to remove a foster child from our home at their discretion,” and, “We agree that visits by the child’s parents, relatives or friends shall be arranged by the agency and not by us.”

In an October 2022 email to the attorney who filed the initial lawsuit, a representative from Loving Houston Adoption Agency said Swann had voluntarily placed her son with the agency and still maintained her parental rights.

The couple who had agreed in their contract to only temporarily care for Swann’s son later felt they had to sue for custody of Swann’s baby, according to their attorney, Sherri Evans of the Houston law firm Crain Caton & James. Evans said the couple had previously fostered several children and initially had no intention of adopting when they signed the Loving Houston contract. The Observer is not identifying the couple to protect the child’s privacy.

But Evans told the Observer that the couple was concerned about how visitations were being handled.

In an internal Loving Houston Adoption Agency report filed in the court case, the agency claims that in September 2022, the wife was expressing concern for Swann’s son’s safety during visits at Santa Maria and suggesting reunification was moving too fast. The couple’s initial goal in filing a lawsuit was to replicate DFPS protocols, Evans said. In their legal filings, they asked the court to require Swann to obtain psychological evaluations, do drug testing, and receive parenting coaching before she could regain full custody of him, she said.

“In their minds, they were still thinking the way you do in the foster care system … that you’ve got to do all these different things to keep the baby safe, just like you would in any other [child welfare agency] case,” said Evans. “And that wasn’t happening.”

But the couple’s actions sought to compel Swann to meet additional goals beyond the things she was already required to do by a Harris County court. To respond to the civil lawsuit, she was forced to find an attorney to represent her and regularly meet with attorneys and a judge at the distant Fort Bend County Courthouse.

Cebrun argues that Swann did her best, within her limited means, to meet the benchmarks established by the civil court overseeing the lawsuit against her. But even finding reliable transportation to make the 50-mile trip for visitations from her home in Pasadena, east of Houston, to Fort Bend County was a challenge.

“I think she went through periods of hopelessness that she would ever get her son back,” said Cebrun, when asked about suggestions that Swann seemed disinterested in or disengaged from efforts to reunify with her son. If Swann’s child had been taken away by the state, she still would have had to meet conditions set by a judge to reunify with him, Cebrun said, but the state would have provided more resources to her.

In recent years, state leaders have emphasized birth parents’ rights in such situations. “The Texas Legislature has repeatedly stated its policy goals of reuniting families as often as possible,” state Representative Gene Wu, a Houston Democrat, told the Observer. “We have made it harder to take children away from parents who are simply poor and don’t have a lot of resources but are trying their best. It is unconscionable to take away a child whose parents are trying their hardest.”

Any matter where termination of parental rights is at stake falls under the Texas Family Code—although state child welfare cases are governed by a “completely different section” of the law, said Walter J. Schouten, a Houston family law attorney with Toombs Imel & Associates.

Schouten is not involved in either case described in this story, and he spoke only to general matters of law in an interview with the Observer.

Private foster contracts are mostly “wishful thinking,” said Schouten. They are largely unenforceable in Texas and “In situations where the adoption agency facilitates putting a baby with these hopeful adoptive parents, they can’t guarantee to the biological mother that these other folks aren’t going to come back and seek custody, because you’ve got the law operating on a separate track.”

The contracts offer a kind of a “legal gotcha” to get the cases before a family court judge where they can theoretically petition to terminate a mother’s parental rights on grounds that DFPS would likely not have argued, he said.

In a private lawsuit, foster parents might be able to use a contractual dispute as a springboard to gain access to a civil court and then make arguments for termination of parental rights in a way that wouldn’t normally happen in a state termination proceeding.

But in theory, he said, the U.S. Constitution’s guarantee of due process and family law standards for determining “the best interests of the child” should apply in any legal effort to terminate parental rights.

Over the next two years, the Fort Bend County couple sought to control Swann’s visits and then terminate her parental rights.

In October 2022, Fort Bend County Judge Kali Morgan ordered that the child stay with the couple and issued a “Standing Temporary Mutual Injunctions” order, which instructed all parties not to interfere with the other party’s possession of the child. Family court attorneys say that type of standing order is common in child custody cases.

From early 2023 to mid-2024, the couple had possession of the child and mostly controlled visitation between Swann and her son, with approval of the judge. Simultaneously, Swann was required by the civil court to participate in drug testing, mental health evaluations, and parenting coaching classes.

Then, in September 2024, following a report from an amicus attorney appointed for the child which cast Swann as disinterested in engaging with her son, the couple sought, and the court agreed, to terminate her visits. The couple filed to terminate Swann’s parental rights and adopt her son in early 2025.

By then, the couple had cared for the little boy for nearly three years, and they believed Swann wasn’t achieving the benchmarks and questioned whether she was really committed to parenting her son, according to their attorney.

The case is ongoing.

In February, sitting at the kitchen table in the tidy church-owned transitional home she shares with several other women, Swann fidgeted with a sobriety ring on her finger. “Three years clean,” she said. Throughout an hour-long conversation, she frequently punctuated sentences with “Amen.”

Over the course of several interviews, Swann, now 33, seemed to slowly let down her guard, speaking more in-depth about her life. During a recent conversation, she talked about the challenges she faced growing up in foster care and never knowing her own biological family until she was in her late teens. She was forthright about the mistakes she has made.

She credits her first foster parent with being a good guardian, but she said she ran straight into trouble around middle school. As a younger woman, she’d given birth to another baby, a girl, whom she voluntarily gave up to relatives because she knew she was unequipped to raise her.

“I know she’s well taken care of,” Swann said, her face brightening as she talked about videos the people raising her daughter have shared. “She’s well-loved.”

But this time, she’s older, and she wants a chance to raise her son. It’s not fair to judge her on who she was, she said. She’s a different person now, healthier and sober.

Swann argues that she loves her son, and that family bonds should mean something, while acknowledging the superior financial resources of the family who has had him the past three years. She is grateful for the love and care they have given her little boy, but she desperately wants him back.

“I thank [the woman who is raising him] for what she’s doing with him, how much she’s taught him,” Swann said, choking back tears. “But I wanted to do that myself.”

This article was produced as a project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2025 Child Welfare Impact Reporting Fund. Initial reporting was supported by a grant from the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

(Except for the headline, this story has not been edited by PostX News and is published from a syndicated feed.)