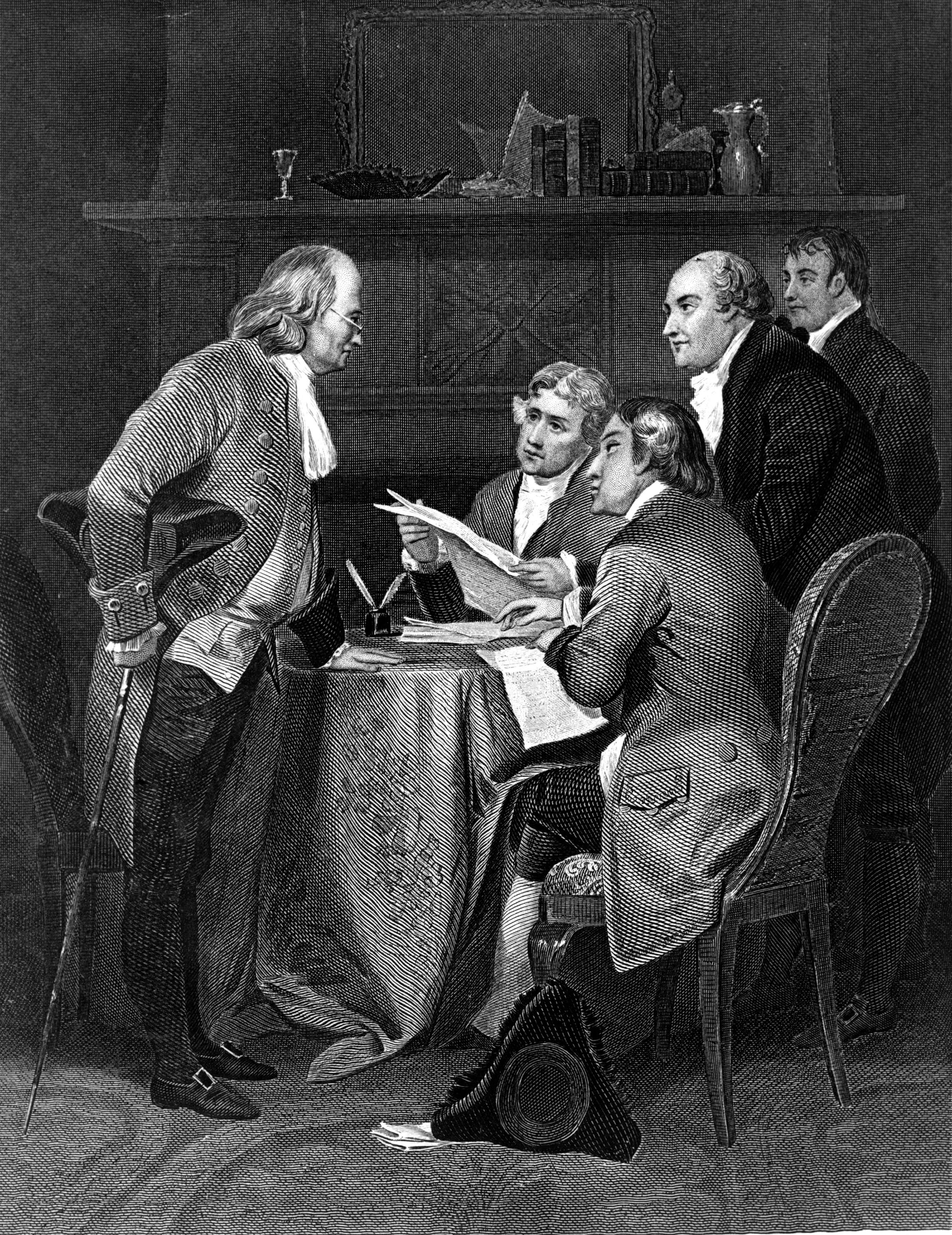

It was the most important writing assignment in world history. In May of 1776, John Adams, an accomplished draftsman who penned the state Constitution of Massachusetts (still the world’s oldest), organized the committee responsible for drafting the Declaration of Independence.

At Adams’ insistence, the committee chose Thomas Jefferson, a mere 33 years old at the time and the youngest delegate to the Continental Congress, to do the drafting. Adams chose him for good reason: Jefferson had written a soaring indictment of King George III two years earlier, a rhetorical masterpiece called “A Summary View of the Rights of British North America,” which addressed the king’s abusive treatment of the American colonists. And the notion of monarchy itself.

“That these are our grievances which we have thus laid before his majesty, with that freedom of language and sentiment which becomes a free people claiming their rights, as derived from the laws of nature, and not as the gift of their chief magistrate: Let those flatter who fear; it is not an American art. To give praise which is not due might be well from the venal, but would ill beseem those who are asserting the rights of human nature. They know, and will therefore say, that kings are the servants, not the proprietors of the people.”

Jefferson ended his entreaty with these words: “The God who gave us life gave us liberty at the same time; the hand of force may destroy, but cannot disjoin them.”

AP Photo

The tide within the colonies had been turning against King George for nearly a decade with the Townsend Acts of 1767, which taxed the colonists on all kinds of essential products. Worse, the British headquartered customs officials throughout the city to serve as collection agents and enforcers of the latest trade regulations.

As King George III got tougher on the colonists, American loyalties further eroded. Things came to a head with the passage of the Intolerable Acts in 1774, including the Quartering Act.

Few people have written more eloquently about those world-altering times—and the cultural context from which the Declaration of Independence was birthed—than Dr. Larry Arnn, author of The Founders’ Key and president of Hillsdale College.

“What sails into Boston Harbor but ships with soldiers on them. And the soldiers get off and bring writs that they can look in general, and in places without naming what they’re looking for,” Arnn said in a speech at the college’s Michigan campus.

“And they bring orders that led to the quartering troops part of the Bill of Rights, which was that they had the right to take over the barracks of the militia. And the militia was the chief defense of the United States. And now their gathering and drilling place was taken from them. And they also had the authority to take over public houses and what were called unoccupied residences. And the person who would judge whether a residence was unoccupied or not was a justice of the peace appointed by the governor, appointed by the king.”

With that experience as a backdrop, Jefferson went to work, drafting a document that was broken into three separate parts. Arnn described what those three parts were about, starting with the first.

It is what you would think the document would be about. It’s a legal assertion of separation. And then the signers pledge their fortunes, their lives and their sacred honor to it. You’d think that would be first, because these are wanted men. And they’re about to go to war, and they know that to lose it is to be hung, and even to fall into the hands of the British on the street is to be deported and probably hung. So you’d think they’d start with that. You’ve been bad to us, and we’re going to fight you.

Arnn next described the middle part, which consisted of the list of grievances catalogued by Jefferson. Because of that list, Arnn explained, the revolution is justified. And the intellectual groundwork for the Constitution is forged.

“Good government would not do those things, and must not do those things,” Arnn noted. “And those things are the essential elements of what came to be the American Constitution. You have to have separation of powers, you have to have representation, and you have to have a limited government. Those are the main themes of the American Constitution. You have to respect people’s civil liberties, and that structure of government is the way by which you do it.”

Arnn saved the first part of the declaration for last.

It begins so universally with the declaration of the rights that everyone has. And its claim is that in any time, people have certain rights that cannot be violated, and those rights are established in what he calls the laws of nature and of nature’s God. It’s saying that in your nature is written your rights, and that no one may govern you except by your effective consent, that you own the government, and that it may not do anything to you except what you agree that it may do.

Here are those magnificent words, words that still echo in the hearts of human beings around the world.

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.”

On July 4, 1965, a young preacher in Atlanta, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., dedicated a part of his sermon to that remarkable paragraph by Jefferson, and to a single word contained within it: the word “all.”

“It’s a great dream,” King began. “The first saying we notice in this dream is an amazing universalism. It doesn’t say ‘some men,’ it says ‘all men.’ It doesn’t say ‘all white men,’ it says ‘all men,’ which includes Black men. It does not say ‘all gentiles,’ it says ‘all men,’ which includes Jews. It doesn’t say ‘all Protestants,’ it says ‘all men,’ which includes Catholics. It doesn’t even say ‘all theists and believers,’ it says ‘all men,’ which includes humanists and agnostics.”

King wasn’t finished. “Never before in the history of the world has a sociopolitical document expressed in such profound, eloquent and unequivocal language the dignity and the worth of human personality. The American dream reminds us—and we should think about it anew on this Independence Day—that every man is an heir of the legacy of dignity and worth.”

On his trip from Springfield, Illinois, to his new home in Washington, D.C., to begin serving as the nation’s 16th president, Abraham Lincoln made stops along the way to rally the nation around the Declaration of Independence—and one word: the word “all.” Perhaps the most notable stop was Philadelphia’s Independence Hall on February 22, 1861.

“I have never had a feeling politically that did not spring from the sentiments embodied in the Declaration of Independence,” Lincoln began. Those words, writers of the day noted, brought the house down. Lincoln went on to mention the word ”all” twice in the short speech, adding that there was something in the essence of the declaration itself that gave “hope to the world for all future time.”

As we celebrate America’s 249th birthday this July 4, it’s worth telling the story behind the document that not only changed American history forever but world history. And worth revering not just the document itself, but the men of consequence who made American independence a reality.

(Except for the headline, this story has not been edited by PostX News and is published from a syndicated feed.)