In 2021, the Republican-dominated Texas Legislature redrew the state’s political maps that determine the lines of power in the Texas House, the Texas Senate, and the representatives in U.S. Congress. Thanks to a decade’s worth of population growth fueled by Latinos, Asian Americans, and African Americans, Texas gained two new congressional seats—bringing the state’s total to 38, second only to California.

From a partisan perspective, the maps were primarily about incumbent protection—one new seat went to Republicans in the Houston area, and one went to Democrats in Austin, while the rest of the existing seats were all made either redder or bluer

From the perspective of racial representation, it was a further continuation of the Texas tradition of maximizing the power of conservative Anglo voters at the expense of communities of color—especially in Houston and Dallas-Fort Worth.

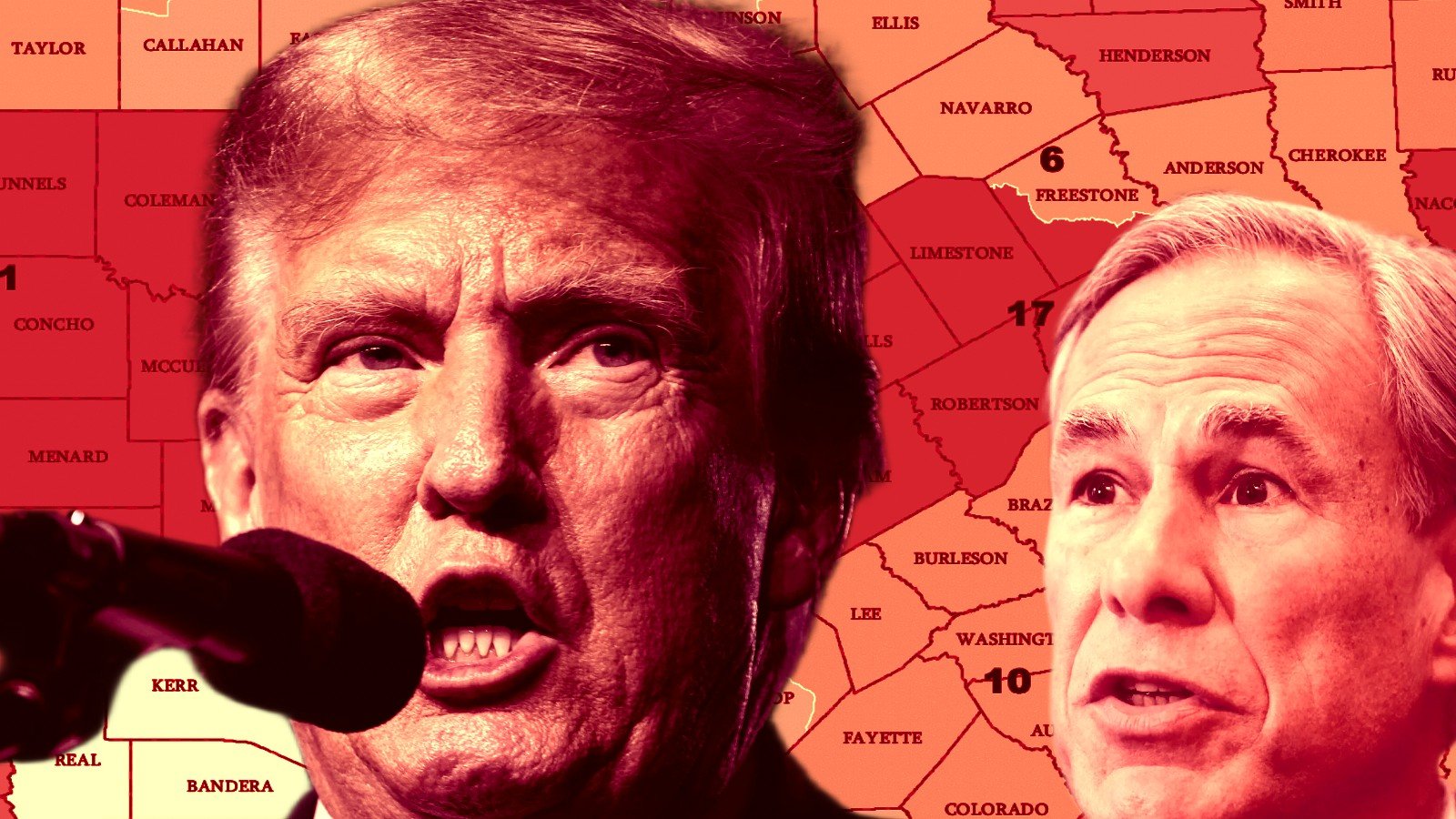

Timing-wise, that re-mapping was done as it typically is: after the decennial federal census. Yet, just four years later, Republicans are—upon receiving orders from their supreme leader President Donald Trump—coming back to Austin for a second bite at the gerrymandering apple as Team MAGA hopes to shore up its razor-thin majority in the U.S. House in 2026.

Governor Greg Abbott has put redistricting on his call for the current special legislative session, which convened Monday, citing the need to address constitutional concerns around a few specific racially gerrymandered congressional districts in Houston and DFW (something Trump’s Department of Justice quite conveniently chose to criticize and about which the Texas GOP has never before cared).

There are reports that Republicans will try to redraw as many as five currently Democratic districts—from South Texas and Houston to Dallas and possibly Austin—to favor the GOP to flip in the upcoming midterms.

That’s a tall task and a politically dicey maneuver—and one we saw 20 years ago. The Texas Observer spoke with Michael Li, a Texas native and longtime redistricting expert at the Brennan Center, about Tom Delay, dummymanders, and the long history of racial gerrymandering in the state.

TO: Texas was sued in 2021 for violating the Voting Rights Act by racially gerrymandering its new maps. Can you give a brief overview of what’s transpired since then?

The trial on the challenges to the 2021 map just concluded in June. … The briefing on that will continue into the fall and at some point in the coming months the court will rule. But of course, in the interim, some of those claims could be mooted out with respect to the congressional maps. So the [state] legislative map claims could still go on, but the congressional could become moot if the state draws new maps. So it’s this sort of bizarro world—this is the world without Section 5 of the [Voting Rights Act], where we had preclearance.

And we’re at the point now in 2025 where the state’s maps have kind of been under litigation for decades now.

Well, every map since the 1970s has been challenged or redrawn in part because they were racially discriminatory or violated the Voting Rights Act. This is nothing new for Texas. Whether Democrats drew the maps or Republicans drew the maps, Texas has struggled for decades to draw maps that fairly represented communities of color.

And in this decade, the map, I think to most objective observers, underrepresents communities of color—who are 95 percent of the population growth [of the] last decade. So you already under-represent those communities, and by redrawing this map you could make a bad map even worse, as hard as that is to believe.

So there were rumblings over the past month of the Trump administration pressuring Republicans in Texas to redraw the maps again, to expand their numbers in the U.S. House. Obviously that has now become a concrete thing. But, you know, we saw this DOJ letter that, right before Abbott put out his special session agenda, specifically lists racially gerrymandered districts in Houston and the DFW area that the state needs to correct. What do you make of that? Was this just a blatant way to create a pretext for Texas Republicans to open up the maps again?

Well, the letter feels very pretexual. It’s hard to make sense of the letter from a legal perspective. Just because you have districts with a lot of minorities and different minority groups doesn’t make it a racial gerrymander. What you have to do for a racial gerrymander is that race has to dominate in how you decided to draw the map. Texas has insisted throughout the [El Paso] litigation that it couldn’t be a racial gerrymander because they didn’t consider race. Race could not predominate if you didn’t consider it.

The letter doesn’t make any sense legally, it doesn’t actually make sense factually, and the fact that the state is using that letter to reopen up the map-drawing process I think is very pretextual.

Because if it was true that, as the state has claimed, there was no racial component to the drawing of the maps, then they could ignore the letter and say “Sue us.”

Right, and in fact Ken Paxton’s office even responded to the letter saying, “No, no, no, we didn’t consider race at all. We did this for partisanship.” Well, that’s fine. If you did it for partisan gerrymandering and you didn’t consider race at all, there is no constitutional problem with these districts. But the fact that Governor Abbott has said [in his special session call], we need to have constitutionally drawn maps—certainly their grasping onto the letter feels like a convenient excuse to do something that [they] already wanted to do for other reasons.

We’re hearing that Republicans want to add as many as five more districts, but that does not necessarily mean that they’re going to target the ones that are named in the DOJ letter. It gets messy very quickly, there’s all these cascading effects with changing lines and stuff, but they can kind of just open up the maps entirely and just start changing everything.

Yeah, I don’t think they’re bound by those districts alone. If you actually redraw the districts that are named in the letter, that’s just buying like a Texas-sized legal fight. You’re just inviting the argument that you’re intentionally discriminating against communities of color because these are in many cases long-standing districts that have been represented by Black and Latino members.

And it’s worth mentioning that, last decade, Texas was found by a three-judge panel in Washington [to have] intentionally discriminated when it drew its maps. The court in the preclearance case said, like, there’s more evidence of intention to discriminate than we have room or need to discuss. So there’s a lot of danger in attacking these districts.

Reports have said the GOP’s tentative plan to draw new Republican seats would be to target districts in South Texas, Henry Cuellar’s district and Vicente Gonzalez’s, Julie Johnson’s district in the Dallas area. The Houston area, and potentially in Austin. In terms of just the partisan gerrymandering aspect of this, does that strike you as especially aggressive?

From both a partisan perspective and a racial perspective, many of those are majority non-white districts—with the exception of Lloyd Doggett’s district in Austin. So you’re talking about targeting the political power of communities of color in a pretty aggressive way. But it’s also aggressive politically. Republicans in Texas already hold two-thirds of the congressional seats. If they add another five, they end up with 80 percent of the seats—in a state where they get around 55-56 percent of the vote at best.

This has “dummymander” written all over it. And again, last decade is a cautionary tale. [Republicans] drew the maps very aggressively last decade and it looked pretty good for them. And then [in 2018] they lost the Dallas seat that Colin Allred won and the Houston seat that Lizzie Fletcher won, and they almost lost a bunch of seats around the Austin area. Texas is growing so fast, it’s changing so fast, it’s becoming more diverse so fast. So it’s really hard to predict what the future electorate of Texas looks like. Because when you gerrymander, you’re making a bet that you know what the politics of a place are going to be.

And in many places, that’s true because, you know, they’re not changing that much. In Texas, it’s just the opposite of that. You can easily be too smart for your own good..

Right. And in 2021 with the current set of maps the consensus was it was a Republican-favored map where they expanded their numbers a bit but it was fairly tempered compared to past maps and was more about protecting the current status quo for incumbents. And then they saw 2022 and 2024 where Republicans won at big levels statewide and saw specific gains in South Texas in the Valley and some backsliding in the suburbs like Fort Bend and Collin counties. So it feels like they’re kind of looking back and being like, “Damn, we should have been more aggressive.” And they’re at risk of short-term political gain right now based on potentially over-reading or over-interpreting what could be some electoral aberrations.

Yeah, that’s absolutely right. If you talked to a lot of Democrats after 2018, they thought they knew what the future of the state was going to look like. They were wrong.

They were pretty confident that they were going to flip the Texas House in 2020. And that didn’t happen.

Right, and 2022 and 2024 were certainly good for Republicans, but things have changed. One being Joe Biden is no longer President and Donald trump is. And if you were trying to be in a good position for the rest of the decade, you might not want to be so aggressive.

But maybe they’re thinking this will be good enough for 2026 and we may lose seats in ’28 or ’30, but oh well. That is the world that the Supreme Court left us in because they said: partisan gerrymandering, we’re not gonna police it.

So the last time, infamously, that something like this happened was back in was in 2003 with Tom Delay in the mid-decade redistricting where they came to Austin and redid the congressional maps with explicit intentions of packing and cracking Democratic districts, really gutting the entire base of the existing conservative rural Democratic members, and also breaking up Austin into seven different pieces or whatever. What do you see as key similarities and differences with the situation now?

A key difference is when they redrew the maps in the 2000s, it was to replace a court-drawn map. The Legislature had deadlocked in 2001 because the Democrats still controlled the Texas House and they couldn’t agree on a map and so a court drew a map. And the court took a conservative approach in terms of not making a lot of changes based on the 1991 maps. … And the 1991 map was a fairly infamous and aggressive Democratic gerrymander, because Democrats controlled the process in 1991, and so by the early 2000s Republicans were winning the majority of the state vote but Democrats still controlled a majority of congressional seats. Republicans thought well that seems unfair. … Whether you agree with how aggressive they were or not, they did sort of have a case. This decade it’s different right, because Republicans drew this map. They got what they wanted and now they’re redrawing it. I can’t think of another example in the country where a party redraws the map that it drew. … That’s really unprecedented.

And also, going back to the point, if you accept the premise of the 2000s that seat share and vote share should kind of be alike, well Republicans have 67 percent of the seats. They don’t win 67 percent of the vote—and they certainly don’t win 80 percent. If you accept the arguments from the Tom Delay cycle, well gosh you actually should have more Democratic seats.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

(Except for the headline, this story has not been edited by PostX News and is published from a syndicated feed.)