Until July 29, the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze hosts Originali. “I manoscritti dei poeti d’oggi” e le poetiche verbo-visuali in Italia, a landmark exhibition celebrating the legacy of Italian visual poetry and Lamberto Pignotti, its most incisive and enduring figure. At once a retrospective and a critical intervention, the show reveals how visual poetry in Italy emerged not merely as aesthetic play, but as a cultural resistance movement. Through manuscripts, collages, artist books and curated dialogues with works from the library’s famed collection, Originali reconstructs the intellectual and political fabric of the verbo-visual tradition and invites us to ask a timely question: What happens when the techniques of visual poetry migrate into the digital age, from memes to AI-generated word-image hybrids? Do they echo the radical intentions of their avant-garde ancestors or betray them?

The roots of visual poetry run deep in 20th-century avant-garde. Italian Futurism, under Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s guidance, was among the first movements to test the boundaries of the page. With parole in libertà (words in freedom), Futurists transformed poems into dynamic typographic compositions, celebrating the speed, violence and chaos of modernity and industry. As the century progressed, Dada pushed this further, introducing collage and nonsense verse as a means of confronting the absurdity of the post-war world. Italian visual poetry inherited this experimental legacy, but took it in a critical direction.

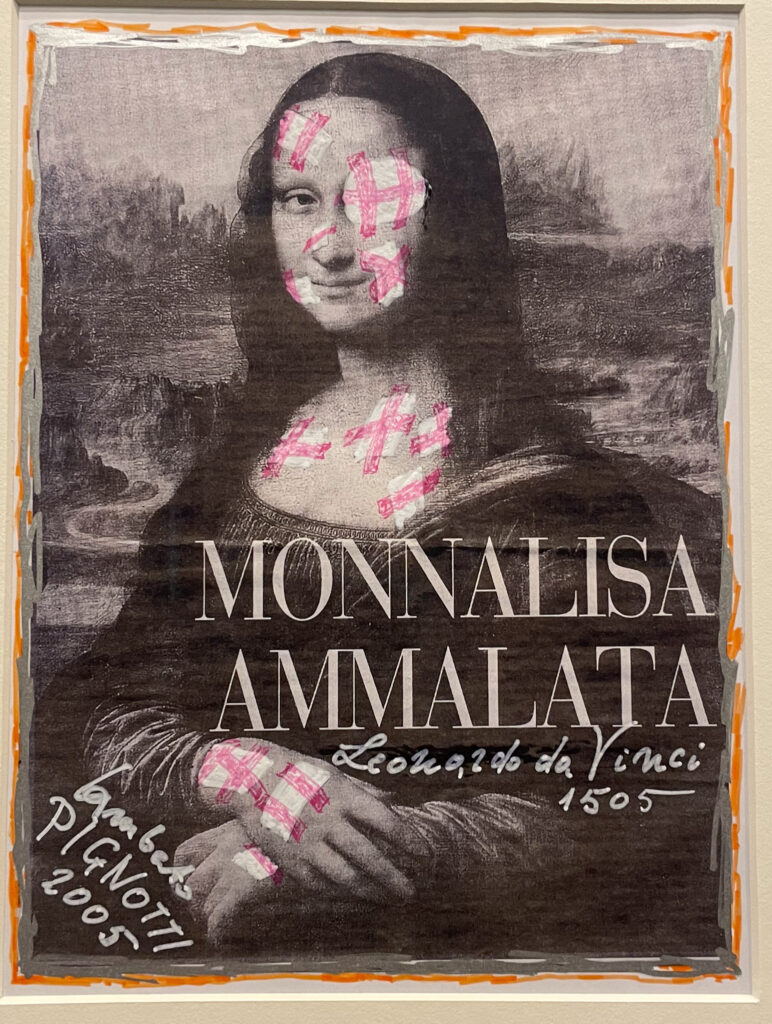

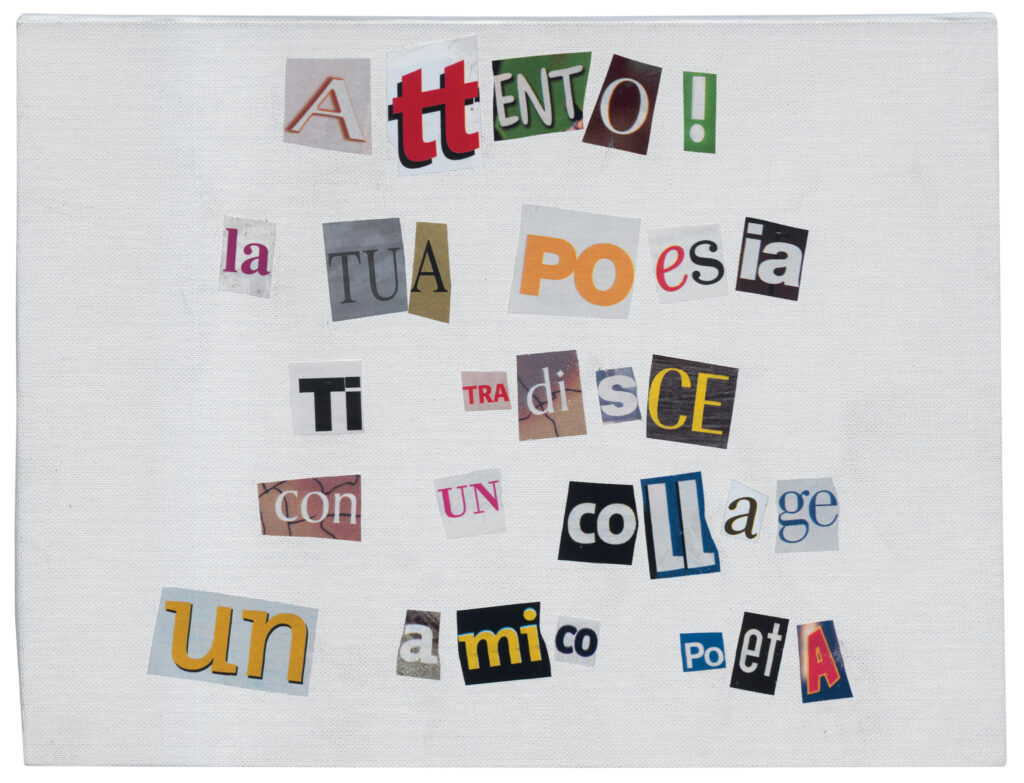

Lamberto Pignotti debuted in the postwar period, shaped by the vibrant atmosphere of post-hermeticism in Florence. In the 1950s he came into contact with a group of writers and intellectuals who had begun to explore the relationship between poetry and painting. From his encounter with Eugenio Miccini arose the first experiments combining linear poetry and images drawn from emerging mass culture, which formed the foundation of Gruppo 70, dedicated to reimagining poetry for the age of television and advertising. Their poetry was confrontational, taking the glossy surfaces of magazines and newspapers, undermining them with irony, contradiction and collage.

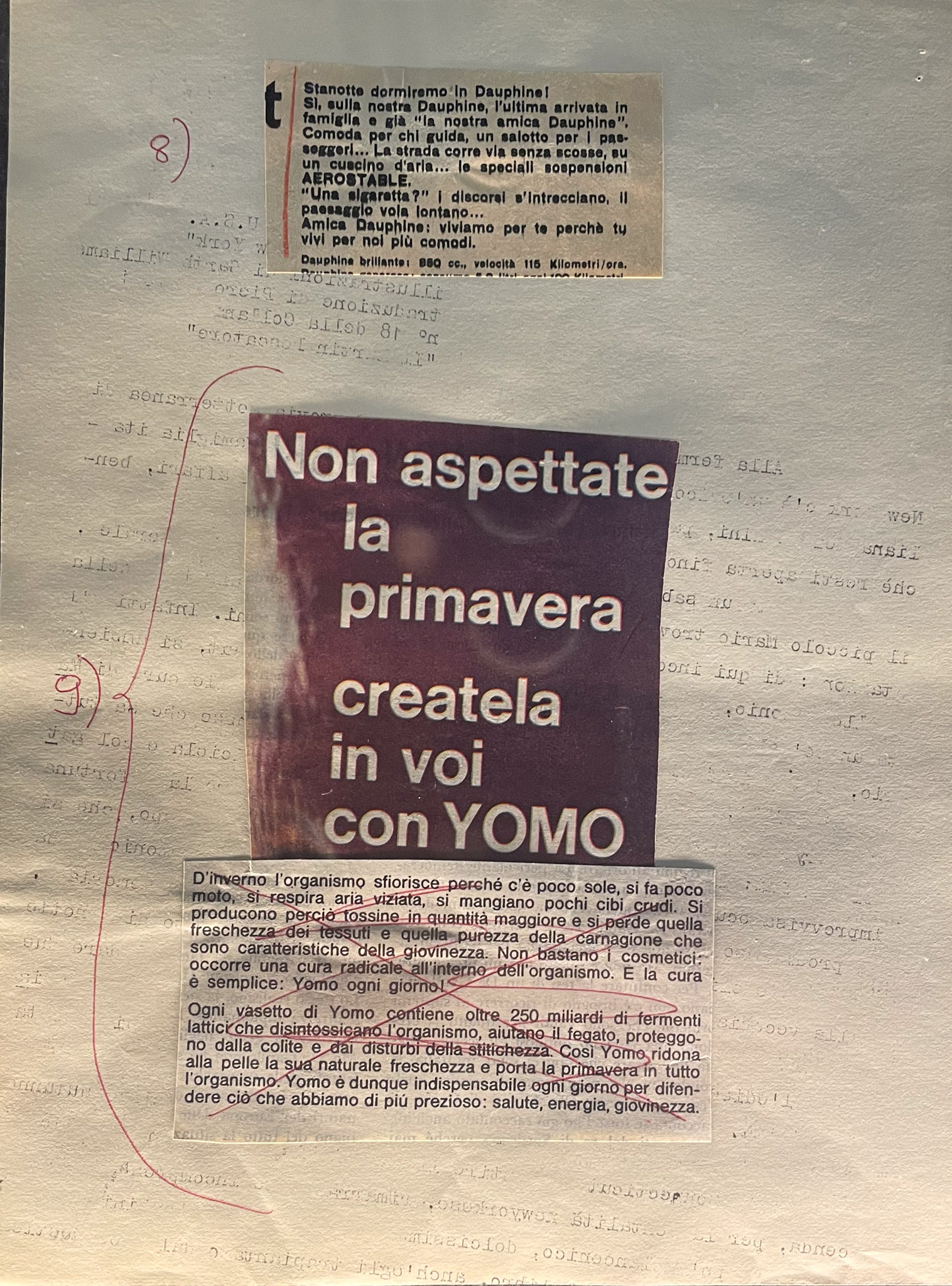

In this, Italian visual poets moved beyond Futurism’s fetish for modernity and Dada’s chaotic rebellion. They adopted the media-awareness of Umberto Eco, who in his essay Apocalittici e integrati argued that mass media was not just a transmitter of ideology—it was ideology itself. Visual poetry, in turn, became a site of semiotic warfare. By treating the poem as a place to confront the overproduction of meaning in late capitalist society, they were spiritual cousins of Guy Debord, whose The Society of the Spectacle (1967) declared: “The spectacle is not a collection of images; it is a social relation between people that is mediated by images.” Pignotti and his peers internalized this insight long before it became fashionable: their poems are détournements, subverting the messages of commerce and power from within.

At the Originali exhibition, many of these works are revisited and juxtaposed with artist books and early manuscript drafts that reveal not only the final product, but the thought process: margins scrawled with changes, slogans revised for sharper bite, a word swapped to shift the tone from irony to accusation. Fast-forward to today, and we find the techniques of visual poetry alive and well—on memes and in AI-generated content. The structural DNA is unmistakable: brief text layered over evocative imagery, built for sharing and remixing.

Today’s digital formats democratize the visual-poetic impulse, enabling anyone to create short, resonant, layered works, but without the critical intent of their forebears, much of this output risks becoming aestheticized noise, style stripped of subversion. As AI tools generate increasingly sophisticated visual poetry, they often do so without awareness. Visual poetry once stood against the spectacle; AI risks becoming its most seductive servant, mimicking the form while draining it of its content. An example of this is the recent Italian Brainrot meme wave, a form of audiovisual poetry purposefully stripped of any meaning.

This is why Originali matters now. Curated by Giovanna Lambroni and David Speranzi, the exhibition doesn’t just historicize visual poetry—it places it in dialogue with the present. Pignotti’s archive, recently acquired and declared of national cultural importance, is not only a record of past practice, but a manual for contemporary resistance. The exhibition invites us to consider what it means to write poetry in an age where every image is engineered to persuade. How do we fight back when even our tools are learning to mimic irony?

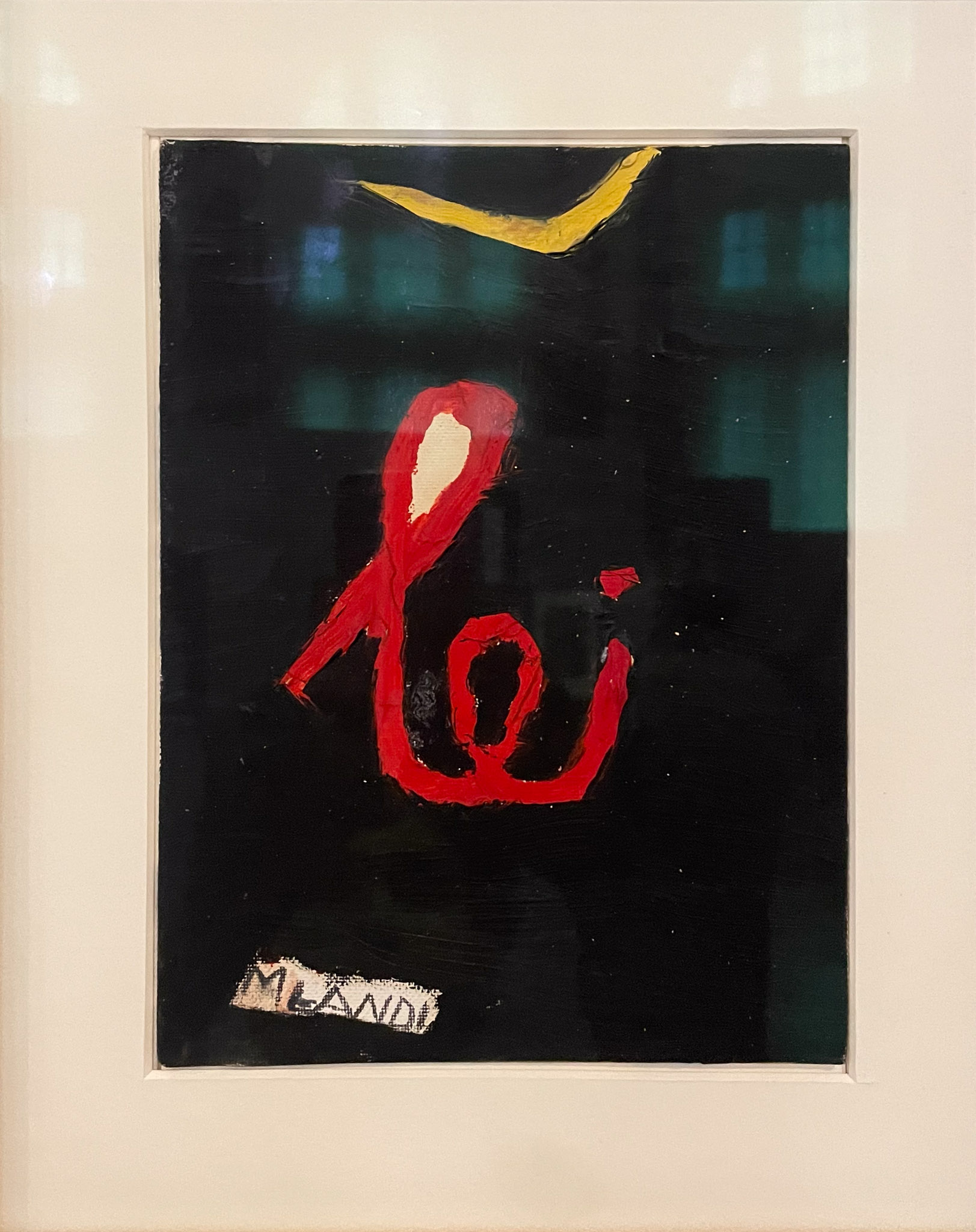

She

Don’t wait for spring! Create it within you with YOMO yogurt.

jQuery(document).ready(function(){ galleryBlock(); });

As viewers move through Originali, they encounter not only poems and books, but an ethics of creation; a belief that the visual arrangement of words can challenge power, expose ideology and reclaim meaning—and that belief feels more urgent than ever.

Visual poetry in Italy was never only about art, but also about media and control. In the hands of Pignotti and his peers, the poem became a subversive device shaped by theory, sharpened by irony and unleashed on the systems of mass communication. Today, those techniques survive in memes and digital collages. But are we still able to use the visual word to reflect and resist the spectacle?

Until July 29, Originali offers not only a historical answer, but an invitation: to write, read, and look with vigilance.

The post The visual word at the National Central Library appeared first on The Florentine.

(Except for the headline, this story has not been edited by PostX News and is published from a syndicated feed.)